Blogging Against Disablism Day, 2011 -- growing archive (click to see what others are writing).

[Author's note: in this article, I am citing ancient Greek myth and epithets, so I'm primarily using the terms "crippled" and "Lame," rather than "physically disabled" or "mobility impaired."]

There are two primary meanings of the word "myth." The first meaning is: "a sacred and ancient story that reflects a deep truth about the world and our place in it." The second is: "a falsehood that we deeply

wish to be true." Often, those two meanings overlap, and the false myths we tell about ouselves can skew our understanding of the sacred myths of those who came before.

And this is what typically happens around the myths of Hephaestus, the ancient Greek god of metalwork, the forge, and craftsmanship ("Vulcan" to the Romans), who was also "The lame one," and "of Crooked Feet". Wayland, the Norse god of the forge was also lame, and this attribute of both the gods may trace back to their common Indo-European roots. But for this article, I will focus on Hephaestus.

The sacred story myths of Hephaestus overlap with the wishful thinking myth of our own time, namely that the "Issue of Disability" is a modern phenomenon, and something we've only started to confront in the last few generations. In ancient times, we tell ourselves, disability as we understand it just didn't exist. Any infant who was born too early or too small was taken out to the wilderness and left to die. The same was true of the elderly, or those grievously wounded by accident.

Sure, it may be less than ideal that we put our disabled into institutions, or deny them access to jobs or schooling, but at least we give them food and shelter and medical care. The ancient Greeks may have been the pinnacle of civilization for their age. But we're even better, more filled with Christian Charity than they were in this regard. They may have called one of their gods "lame" and "crippled," but that just meant that he walked a little bit funny, and was less graceful or handsome than Apollo or Zeus. It certainly didn't mean that he was

actually impaired. He couldn't have been. He was a god.

The Greek Gods. Just the mention of them conjures up images of physical perfection, strength and beauty. They are, in modern Western culture, the archetypes of archetypes: understood as the rootstock of literature and psychology.

So imagine my surprise, when, in high school, I was reading through an illustrated encyclopedia of mythology for young readers, and I came across the story of Hephaestus -- the god of metalworking, the forge, and crafts. In the version of the story I read, he came between his parents, Zeus and Hera, during one of their frequent fights, and sided with his mother.

Zeus, the ruler of the gods, did not take this well, and threw Hephaestus off Olympus, who was then falling for a whole day and night, and when he landed, he became crippled, and unable to walk from then on. He used his skills as a metalworker to build himself four golden handmaidens support him as he walked, and to help him in his workshop (Perhaps the first example of "robots" in the Western Tradition).

It has been many years, now, since I first encountered this story, so I can't recall with one hundred percent accuracy, but I may have giggled as I read it -- or at least, grinned like the Cheshire Cat. This was a

god -- a Greek god, to boot -- who was far from perfect, who needed to build himself automaton maidens to help him walk, and who, (it would seem, from this version of the story) suffered and survived the very mortal accident of a spinal chord injury, with its very mortal consequences. Here, at last, was an archetypal representation for me, nestled in among the archetypes of perfect humanity.

Sometime later, I read a second Hephaestus myth: that he had no father -- that Hera, jealous that Zeus had birthed the goddess Athena without her, decided to birth a child without

him. Her anger, bitterness and jealousy infected her son, and he was born deformed. In shame and disgust, it was Hera who threw him off the mountain as unfit to live on Olympus. This version of the myth corresponds more closely with my own experience on the one hand, since Hephaestus was born disabled, but on the other, his level of disability is more ambiguous -- he was simply "too imperfect" to be in the company of the other gods, and was therefore rejected.

This is the version that corresponds to our modern concept that the ancient past was barbaric and cruel: a mother who would throw her own child to his supposed death.

We don't do that, we tell ourselves (except, sometimes, we do).

So, which interpretation of the myth was correct? Was it my first reaction, as a teenager, that took "crippled" at face value to mean the same thing way back then as it does today? Or was it the more jaded view, that says life back then was so brutish and short that it couldn't possibly mean the same -- that anyone who fell short of an athletic, "Olympic", ideal was labeled as defective?

A couple of years ago, armed with Google Search, I decided scratch that curiosity itch. Most of the images that came back, for the first few pages, seemed to confirm the second interpretation. All the statues of Hephaestus looked as hale and hardy as any of his divine siblings; the only visible nod to his mythic lameness might be that he was shown putting less weight on one foot than the other. Or else, even though perfectly formed, he was shown working at his forge while sitting on a bench or chair.

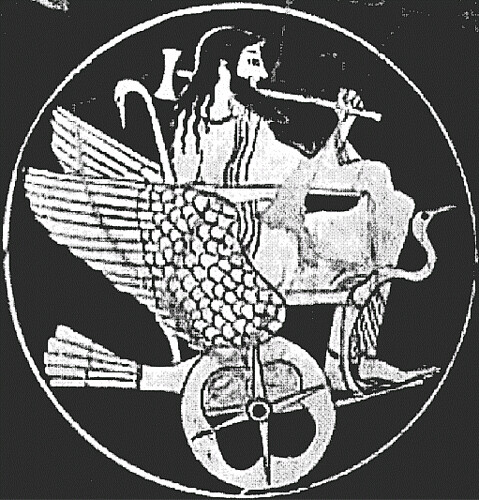

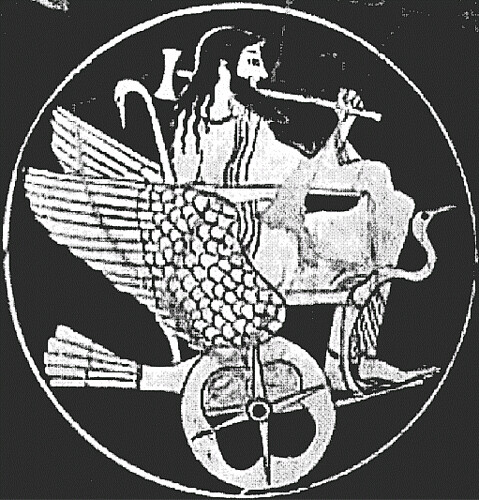

And then, I came upon the photo of a painting from an archaic drinking vessel, dating to somewhere in the sixth century B.C. It showed Hephaestus in a winged chair with wheels. What struck me immediately was how like a modern wheelchair this vehicle was in its proportions (not counting the massive wings sprouting from each wheel, or the matching bird's tail feathers counterbalancing the rear).

Image:

(caption: Black and white image of Hephaestus in a winged, wheelchair-like chariot, adorned with crane motifs, within a white circle; from circa 525 B.C.E)

Now, in context, paintings on these types of vessels (called Kylix) were often meant to be laughed at by drunken humans: Zeus getting caught in one of his many affairs with mortal women was a common motif, for example. So this image of a god riding in a chair with wheels was meant to be an image of mockery and derision. But the artist who painted that image was able, at least, to imagine what sort of assistive technology a person (or god) would need if they really, actually, could not walk.

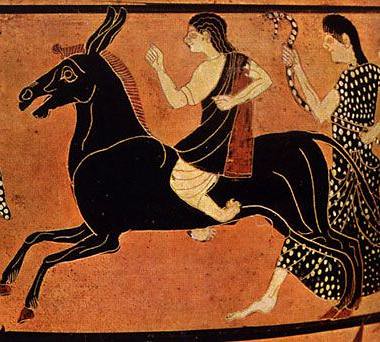

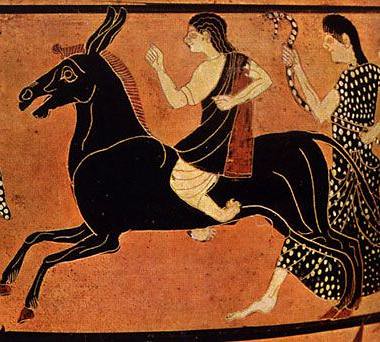

And recently, I found another image of Hephaestus, from roughly the same period, depicting the scene where he is being led back to Olympus on a donkey. It's a commonly painted scene; in most such scenes, the god looks perfectly able-bodied, if a little tipsy from Dionysus's wine. But in this particular image, his deformity is striking: his lower legs are severely shrunken, his feet are half-formed, seem to be missing several toes, and they are turned around backward at the ankles. There is no way someone with legs like that could walk with nothing more than an "unsightly limp." Such a being would need canes, crutches, or if he had the power to create them, automaton handmaidens to support him on each side as he walked, or a golden, flying wheelchair to carry him to the top of a mountain.

Image:

(caption: Color photo of an archaic water jar detail: painted image of Hephaestus riding on a donkey. Both lower legs are depicted as shrunken and deformed. Circa 530 B.C.E.)

These images are in the minority in the archaeological record, as far as I know. But depictions of the disabled are relatively rare in our own day, too, and for much the same reasons; if you have difficulty standing for long periods of time, you are not likely to work as a model in a sculptor's studio. And if, for this reason, you are an artist who is only familiar with "ideal" bodies, you're probably going to guesstimate what a crippled body should look like. If there is a social taboo around the existence of disability, you may be reluctant to fully depict what you

can imagine,

especially when a god is the subject. But if you happen to have disability as part of your lived experience (either directly, or through life with a disabled family member), you will more likely show that in your art.

In relatively recent years, as the fields of archeology, multicultural studies, and modern medicine cross, there's been a trend of looking at all the instances of lame smith gods, and asking if there was something about the ancient craft that

causes the disability -- lead and arsenic poisoning seem to be the leading hypotheses (See the Google Scholar results page

Ancient metallurgy and Lameness for examples).

This is a step in the right direction. But this approach still presumes that any impairment or disability in ancient times was acquired -- not something anyone lived with and adapted to from the start. And there are no symptoms of Hephaestus being otherwise sickly or poisoned in his myths -- simply that he cannot walk far without assistance. It

could be that working at a forge was something a person could do while seated, with a workshop full of apprentices, should you need extra help -- as Hephaestus was depicted in so many vase paintings, frescoes and murals.

And I know, from personal experience, that living in a mobility-impaired body leads you to inventive thinking, and building new tools on the spot ("Oop! Dropped my pencil, let me get my grabber... Darn! dropped my grabber. What

can I reach? And how can I use that cobble something together to get the things I can't?"). It's not hard to imagine that the first hammer was invented by someone who lacked the hand or arm strength to smash open a marrow bone or nut with a rock alone... And then, others in the clan kept finding reason to borrow it, and make their own. Seen in this way,

all technology is assistive technology. And maybe, even in our advanced civilization, we need diverse ways to move through the world as much as we need a diverse genome.

So maybe the ancients

did mean the same thing as we do, when they spoke of someone being "crippled" and "lame." Maybe it's time to acknowledge that disability has been a part of human culture from the beginning. Maybe it's time to discard the notion acknowledging the disabled is enough. Maybe, after twenty-five centuries, it's time to raise the bar.

For more details on the Hephaestus myths, quotes from literature, and a gallery of Hephaestus images, go here:

Hephaistos pages at www.theoi.com.