[Author's note: in this article, I am citing ancient Greek myth and epithets, so I'm primarily using the terms "crippled" and "Lame," rather than "physically disabled" or "mobility impaired."]

There are two primary meanings of the word "myth." The first meaning is: "a sacred and ancient story that reflects a deep truth about the world and our place in it." The second is: "a falsehood that we deeply wish to be true." Often, those two meanings overlap, and the false myths we tell about ouselves can skew our understanding of the sacred myths of those who came before.

And this is what typically happens around the myths of Hephaestus, the ancient Greek god of metalwork, the forge, and craftsmanship ("Vulcan" to the Romans), who was also "The lame one," and "of Crooked Feet". Wayland, the Norse god of the forge was also lame, and this attribute of both the gods may trace back to their common Indo-European roots. But for this article, I will focus on Hephaestus.

The sacred story myths of Hephaestus overlap with the wishful thinking myth of our own time, namely that the "Issue of Disability" is a modern phenomenon, and something we've only started to confront in the last few generations. In ancient times, we tell ourselves, disability as we understand it just didn't exist. Any infant who was born too early or too small was taken out to the wilderness and left to die. The same was true of the elderly, or those grievously wounded by accident.

Sure, it may be less than ideal that we put our disabled into institutions, or deny them access to jobs or schooling, but at least we give them food and shelter and medical care. The ancient Greeks may have been the pinnacle of civilization for their age. But we're even better, more filled with Christian Charity than they were in this regard. They may have called one of their gods "lame" and "crippled," but that just meant that he walked a little bit funny, and was less graceful or handsome than Apollo or Zeus. It certainly didn't mean that he was actually impaired. He couldn't have been. He was a god.

The Greek Gods. Just the mention of them conjures up images of physical perfection, strength and beauty. They are, in modern Western culture, the archetypes of archetypes: understood as the rootstock of literature and psychology.

So imagine my surprise, when, in high school, I was reading through an illustrated encyclopedia of mythology for young readers, and I came across the story of Hephaestus -- the god of metalworking, the forge, and crafts. In the version of the story I read, he came between his parents, Zeus and Hera, during one of their frequent fights, and sided with his mother.

Zeus, the ruler of the gods, did not take this well, and threw Hephaestus off Olympus, who was then falling for a whole day and night, and when he landed, he became crippled, and unable to walk from then on. He used his skills as a metalworker to build himself four golden handmaidens support him as he walked, and to help him in his workshop (Perhaps the first example of "robots" in the Western Tradition).

It has been many years, now, since I first encountered this story, so I can't recall with one hundred percent accuracy, but I may have giggled as I read it -- or at least, grinned like the Cheshire Cat. This was a god -- a Greek god, to boot -- who was far from perfect, who needed to build himself automaton maidens to help him walk, and who, (it would seem, from this version of the story) suffered and survived the very mortal accident of a spinal chord injury, with its very mortal consequences. Here, at last, was an archetypal representation for me, nestled in among the archetypes of perfect humanity.

Sometime later, I read a second Hephaestus myth: that he had no father -- that Hera, jealous that Zeus had birthed the goddess Athena without her, decided to birth a child without him. Her anger, bitterness and jealousy infected her son, and he was born deformed. In shame and disgust, it was Hera who threw him off the mountain as unfit to live on Olympus. This version of the myth corresponds more closely with my own experience on the one hand, since Hephaestus was born disabled, but on the other, his level of disability is more ambiguous -- he was simply "too imperfect" to be in the company of the other gods, and was therefore rejected.

This is the version that corresponds to our modern concept that the ancient past was barbaric and cruel: a mother who would throw her own child to his supposed death. We don't do that, we tell ourselves (except, sometimes, we do).

So, which interpretation of the myth was correct? Was it my first reaction, as a teenager, that took "crippled" at face value to mean the same thing way back then as it does today? Or was it the more jaded view, that says life back then was so brutish and short that it couldn't possibly mean the same -- that anyone who fell short of an athletic, "Olympic", ideal was labeled as defective?

A couple of years ago, armed with Google Search, I decided scratch that curiosity itch. Most of the images that came back, for the first few pages, seemed to confirm the second interpretation. All the statues of Hephaestus looked as hale and hardy as any of his divine siblings; the only visible nod to his mythic lameness might be that he was shown putting less weight on one foot than the other. Or else, even though perfectly formed, he was shown working at his forge while sitting on a bench or chair.

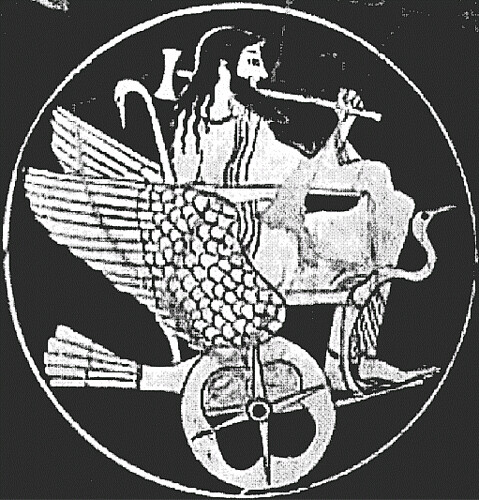

And then, I came upon the photo of a painting from an archaic drinking vessel, dating to somewhere in the sixth century B.C. It showed Hephaestus in a winged chair with wheels. What struck me immediately was how like a modern wheelchair this vehicle was in its proportions (not counting the massive wings sprouting from each wheel, or the matching bird's tail feathers counterbalancing the rear).

Image:

(caption: Black and white image of Hephaestus in a winged, wheelchair-like chariot, adorned with crane motifs, within a white circle; from circa 525 B.C.E)

Now, in context, paintings on these types of vessels (called Kylix) were often meant to be laughed at by drunken humans: Zeus getting caught in one of his many affairs with mortal women was a common motif, for example. So this image of a god riding in a chair with wheels was meant to be an image of mockery and derision. But the artist who painted that image was able, at least, to imagine what sort of assistive technology a person (or god) would need if they really, actually, could not walk.

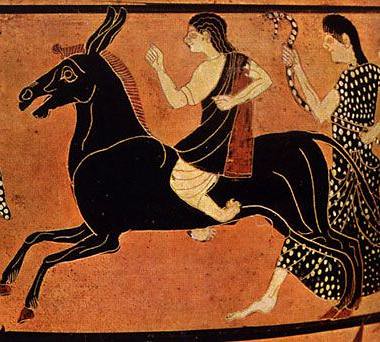

And recently, I found another image of Hephaestus, from roughly the same period, depicting the scene where he is being led back to Olympus on a donkey. It's a commonly painted scene; in most such scenes, the god looks perfectly able-bodied, if a little tipsy from Dionysus's wine. But in this particular image, his deformity is striking: his lower legs are severely shrunken, his feet are half-formed, seem to be missing several toes, and they are turned around backward at the ankles. There is no way someone with legs like that could walk with nothing more than an "unsightly limp." Such a being would need canes, crutches, or if he had the power to create them, automaton handmaidens to support him on each side as he walked, or a golden, flying wheelchair to carry him to the top of a mountain.

Image:

(caption: Color photo of an archaic water jar detail: painted image of Hephaestus riding on a donkey. Both lower legs are depicted as shrunken and deformed. Circa 530 B.C.E.)

These images are in the minority in the archaeological record, as far as I know. But depictions of the disabled are relatively rare in our own day, too, and for much the same reasons; if you have difficulty standing for long periods of time, you are not likely to work as a model in a sculptor's studio. And if, for this reason, you are an artist who is only familiar with "ideal" bodies, you're probably going to guesstimate what a crippled body should look like. If there is a social taboo around the existence of disability, you may be reluctant to fully depict what you can imagine, especially when a god is the subject. But if you happen to have disability as part of your lived experience (either directly, or through life with a disabled family member), you will more likely show that in your art.

In relatively recent years, as the fields of archeology, multicultural studies, and modern medicine cross, there's been a trend of looking at all the instances of lame smith gods, and asking if there was something about the ancient craft that causes the disability -- lead and arsenic poisoning seem to be the leading hypotheses (See the Google Scholar results page Ancient metallurgy and Lameness for examples).

This is a step in the right direction. But this approach still presumes that any impairment or disability in ancient times was acquired -- not something anyone lived with and adapted to from the start. And there are no symptoms of Hephaestus being otherwise sickly or poisoned in his myths -- simply that he cannot walk far without assistance. It could be that working at a forge was something a person could do while seated, with a workshop full of apprentices, should you need extra help -- as Hephaestus was depicted in so many vase paintings, frescoes and murals.

And I know, from personal experience, that living in a mobility-impaired body leads you to inventive thinking, and building new tools on the spot ("Oop! Dropped my pencil, let me get my grabber... Darn! dropped my grabber. What can I reach? And how can I use that cobble something together to get the things I can't?"). It's not hard to imagine that the first hammer was invented by someone who lacked the hand or arm strength to smash open a marrow bone or nut with a rock alone... And then, others in the clan kept finding reason to borrow it, and make their own. Seen in this way, all technology is assistive technology. And maybe, even in our advanced civilization, we need diverse ways to move through the world as much as we need a diverse genome.

So maybe the ancients did mean the same thing as we do, when they spoke of someone being "crippled" and "lame." Maybe it's time to acknowledge that disability has been a part of human culture from the beginning. Maybe it's time to discard the notion acknowledging the disabled is enough. Maybe, after twenty-five centuries, it's time to raise the bar.

For more details on the Hephaestus myths, quotes from literature, and a gallery of Hephaestus images, go here: Hephaistos pages at www.theoi.com.

Excellent post - well done! My boyfriend is a week away from the final exams of his Classics degree so I have been embedded in this world lately. I have begun to read "The Eye of the Beholder" by Robert Garland which explores attitudes to disabled people in the ancient world.

ReplyDeleteAs with the study of women's history, some of it is utterly awful, but I guess people have always been people, capable of empathy and rebellion. And even when infanticide was common-place, that doesn't mean that it was easy or even possible for all parents.

Anyway, an excellent post. Thank you very much.

I'm glad it came across clearly. I've been living with these ideas for so long, it's sometimes hard to distinguish between what's obvious and what's not.

ReplyDeleteAnd yes -- the old myths and stories are hard to read, sometimes, for their ugly disablism. Then I remember that for every act of disablism, there's a disabled survivor, making his or her mark on the world.

Awesome post, and I love those images, particularly the "wheelchair". Love the classics and fascinated to read about disability and difference in them. It's so interesting how despite the myths surrounding them, Hephaestus is mostly depicted as "normal". Even in myth we don't want to be confronted with difference.

ReplyDelete@Selene -- Well, what is "myth" to us was the foundation of everyday life to the people who lived back then, and humans will be humans, alas. As for the chair -- I know -- I kinda want to take that pic into my mobility equipment shop and say: "One like this, please!" ;-)

ReplyDeleteThis is a reply from Keth, who wrote Researching Disability in Ancient Greece (a wonderful piece, by the way):

ReplyDeleteI was actually thinking when I read what you wrote and saw the picture "no, not like a modern wheelchair but DAMN, i bet a lotta wheelchair

people would love to have one like that!"

Great post, with some really interesting points and insights. (and yes, I will be nabbing the pictures for the presentation to go with the

essay!). I particularly loved your idea of how a hammer (with a handle) came about, I can really see that working, the idea that someone didn't

have the strength to use a hammerstone, so developed a hammer with a handle to give them that strength. I'm reminded of one of my

archaeology classes: we (the whole class) were discussing the wetwang slack chariot burials (a large, iron age cemetary in North Yorkshire,

where a couple of the high status (determined by expensive objects also placed in their graves) individuals were also buried with chariots,

horse equipment, and in at least one case, a couple of horses), and discussing the reason that these high status individuals may have been

buried with a chariot. Our teacher likes to encourage us to think outside the box with regard to what items may be used for, so

eventually, expecting to be shot down, i suggested that perhaps these individuals actually couldn't walk/found it difficult and the chariots were early wheelchairs. To my surprise, she nodded and said that

archaeologists (and, I suppose, historians, as I pointed out in my post) are starting to consider the impact of minority groups like the

disabled in the archaeological record, so its quite possible. and of course that REALLY got me thinking.. heh.. seems all my education ever

does is to provoke thousands of questions in my mind!

anyway.. thank you for a very very interesting post!

Goldfish - I actually read "In the Eye of the Beholder" for my essay, great book. Unfortunately I had to skimread it as i was in the library (couldn't borrow it and the seats were pretty uncomfortable!), so I didn't take in as much as I would've liked. Will have to try to borrow it at some point when I get to Uni.

One book you (and you too, Capri) may want to try to find is "The Staff of Oedipus" by Martha L Rose - I've been able to look at the index and

read part of it on Google Books, but there wasn't a copy in the Uni library i go to, and as an affliate member, I'm not able to request

they borrow books from other libraries. However, the repository libraries in the UK do have copies, and your boyfriend should be able

to request it - although I can quite understand if his mind is elsewhere right at this moment!! If there's one book i regret not being

able to read for my research for my essay, its that one, I would've loved to have gotten my greedy lil mitts on it. ah well.

For various reasons I've read up on a lot of different pantheons of gods over the years and disabled gods turn up time and again. There's Votan, who sacrificed an eye for knowledge, Tyr who lost his hand to the Fenris Wolf, Osiris is missing a very important organ after Set chopped him up and Isis put him back together, but couldn't find one piece, Nuada Silverarm you can probably guess, Sedna (Inuit) had her fingers cut off while trying to hang onto her father's kayak, while the Aztec Tezcatlipoca is missing a foot and may be derived from the Mayan K'awil who is missing a leg.

ReplyDeleteDisability, there's a lot of it about ;)

@DavidG -- indeed. That's why I started this blog: to confront the notion that archetypal stories are only peopled with characters who are archetypically "Whole."

ReplyDeleteMostly, I'll be focusing on folk- and fairy tales, because those are more tightly knotted into our living culture today (thanks to continual retelling in Disney movies, children's reading hours at public libraries, and books on popular psychology). But I'll be retelling some myths, too.

I chose Hephaestus for my BADD post because it intersects more directly with our understanding of real history, and the erasure of disabled people from the human record, which is even more insidous than straight-forward mocking.

Hi Here from your mention on QP forum

ReplyDeleteDo you think disability was "erased from the record" or that modern scholars and archaeologists ignored any references or evidence? I haven't researched this but, given your reference to allowing disabled newborns to die, I wondered whether the survivors got a representative press, just fewer of them.

Thank you for stimulating my mind, Ian

@Ian --

ReplyDeleteWelcome!

It's a complicated question. As another BADD Blogger points out in her essay Researching Disability in Ancient Greece (And no, we in no way colluded!), until very recently, only a very select and privileged minority (White, upper-class, free men of leisure) had access to the writing of history, and their personal biases limited what they thought was worthy of being recorded for history. And once they get established as "experts in the field," their interpretations influence the thinking of the next generation. So it's not so much straight-forward erasing as filtering -- like a polarizing lens that disregards certain events of the past as "Distracting glare".

That's started to change in the last couple of generations, since the disabled have had more access to higher education, and have started to do their own research into history and archeology, because their personal experiences have given them a different insight in interpreting the traces left behind by others.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteWhat’s up friends, its wonderful article concerning educationand completely defined, keep it

ReplyDeleteup all the time.

www.hulu. com/activate – For hulu channel activation, just start with hulu login or starts with hulu activate guide to watch all your favorite movies, TV shows, news, and live sports just a click away at hulu.com/activate and enter hulu activation code.

ReplyDeletewww.hulu. com/activate – hulu activate guide to watch all your favorite movies, TV shows, news, and live sports just a click away at hulu.com/activate and enter hulu activation code.

www.hulu.com/activate – For hulu channel activation, just start with hulu login or starts with hulu activate guide to watch all your favorite movies, TV shows, news, and live sports just a click away at hulu.com/activate and enter hulu activation code.

Roku streaming players are a more convenient and cost effective way to watch live TV. When you power on your Roku device and connect it with the internet, then a Url Roku.com/link will appear on the TV. Then you need to input that Roku activation code by visiting Roku on your computer or mobile screen. All Roku devices need an internet connection.

ReplyDeleteWhen users encounter problems with their HP printers. For instance, the HP printer not printing black, then remove the black ink cartridge from the HP printer using a cotton swab. Clean all the dirt, or dried ink that may be causing hinderance.

ReplyDeleteUpdate your Garmin Express. TGarmin Express update provide the newest updates and installation for all Garmin devices. These Garmin Express Updates add new vital data to your GPS. It will help you save time and fuel while traveling. If you have any doubts, you can call us on Garmin toll-free number. Garmin Express is an outstanding application.

ReplyDeleteGarmin Express is a desktop application to help you manage, update, and set up your Garmin device. For Garmin express update check the about section in settings.free Garmin express map updates for all Garmin device.

ReplyDeletevisite site replica designer backpacks Go Here best replica designer useful reference Louis Vuitton replica Bags

ReplyDeletel3g93d3f95 c5t88y8y47 r1r36f6t79 t3y91a0a71 j2u19x9r37 y4q33y7s87

ReplyDeleteuvvd479ghs

ReplyDeletesupreme outlet

golden goose outlet

supreme outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet