This is my own retelling of the story, based on Google's Auto-Translate from the German, here:

Daumesdick (warning: if you hover your mouse too long over a passage, a bubble pops up with the original language, and asks if you can provide a better translation).

Thumbling (Also Known As: "Tom Thumb")Once upon a time, an old woodsman and his wife sat by the fire one evening; he puffed on his pipe, and poked at the fire while she sat at her spinning wheel and spun.

The old man sighed. "How quiet and lonely it is here! We sit alone in the evenings while our neighbors' houses have children running around, playing and bringing laughter to their families."

"It's true," his wife said, turning her wheel. "I wish for nothing more than a child of my own. Even if it were tiny and no bigger than my thumb, I would love it dearly, and cherish it."

And what do you know -- isn't it odd? Seven months later, the woman fell ill, and gave birth to a tiny baby boy. And the child was no bigger than her thumb.

"Well," the parents said, "it is just exactly what we wished for." They named him Thumbling, and loved him and cared for him as they had promised in their wish.

And though they fed him well, and he thrived, he never grew any bigger than he was the moment he was born. Still, his eyes were bright and his mind was nimble, and he was healthy and as strong as you could wish.

One day, when his father was about to go out into the forest to cut wood for the day, he said: "How I wish I had someone to meet me out there with the horse and cart, to help me bring the wood back."

"I can do it, Father," Thumbling piped up.

His father chuckled. "But you can't even reach the halter," he said. "How could you drive the cart?"

"Well, Mother can hitch up the horse for me, and I can ride in its ear, and tell it just how to go, just as well as you can."

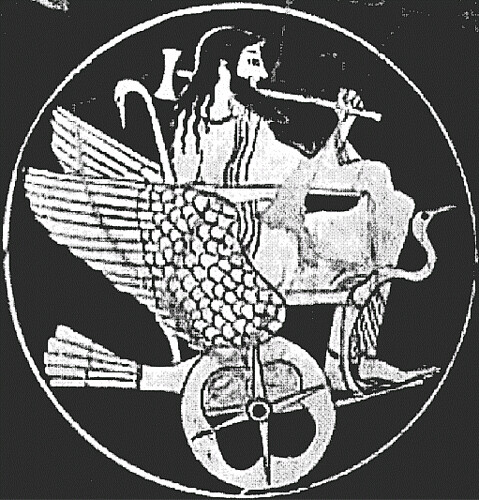

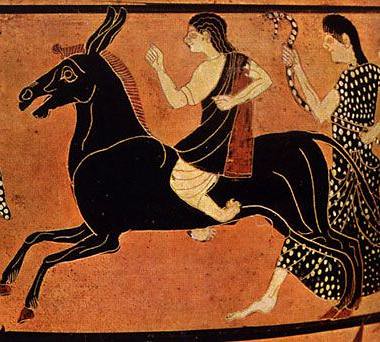

His parents thought that was a very clever plan, and agreed they could try it. His father started out ahead, and then, a little while later, his mother hitched the horse to the cart, and helped Thumbling up into the horse's ear.

And so there he sat -- calling "Gee!" and "Haw!" and "Move up!" and "Whoa!" And the horse moved along and followed direction just as well as if someone had been pulling on the reins.

It just so happened that as they came 'round the corner of the town road, they met two strangers walking the other way, and they happened to pass each other just as Thumbling was calling out: "Gently! "Gently!"

The two men looked at each other. They could clearly see the horse; they could clearly hear

someone. But it seemed as if the driver were invisible.

"What strangeness is this?" one man asked the other. "Let's follow along behind, and see what is going on. I'm sure we'll find something remarkable." And so the two turned around and followed behind the horse and cart.

Soon, Thumbling came up to his father in the woods. "Here I am, Father," he called out, "safe and sound! I told you I could do it."

And his father reached up and took his son from the horse's ear, and sat him down on a straw, which for Thumbling, was quite comfortable.

The two strangers stared at all of this in wonder. Then one whispered to the other. "We could make a fortune, if we had an imp like that -- we could put on a traveling show, and sell tickets; we'd make a fortune."

So they went up to the father and offered to buy Thumbling. "He'd be better off," they said to him. "We could give him a better life than you could."

But his father refused. "I love Thumbling as I love my own eyes," he said. "He's not for sale -- not for all the gold in the world."

But Thumbling climbed up the folds of his father's coat and whispered in his ear: "Go ahead and sell me. But charge a high price. I'll get away from these two and come back home again. I know I can."

So at last, his father agreed, and he traded Thumbling for a purse heavy with gold. And Thumbling went away with the two men.

"What shall I do with you?" the leader of the two asked him.

"Put me on the brim of your hat," Thumbling said. "I can walk around up there, and get a good view of the countryside as we go along."

So that's what the man did. And they walked the whole day until sunset.

"Let me down," Thumbling said. "I have to relieve myself."

"Oh, just do your business up there," the man said. "Birds poop on my hat all the time, and I never even notice. So just go ahead."

"No," Thumbling insisted. "I'm not an animal. "I know what's right. Put me down."

So, finally, the man let Thumbling off the brim the brim of his hat, and put him on the ground. As soon as he was free, Thumbling darted off, and dove into a mouse hole.

The two men, furious, grabbed sticks and tried to force him out, but Thumbling just scampered deeper where the sticks couldn't reach. By then, it was growing dark, and the men had to give up. They had no choice but to return home without their gold, and without their main attraction.

Thumbling crawled out from the hole. "The ground here is treacherous going," he said to himself. "I could fall off a clod of earth and break my neck in the dark. I'd better find someplace to sleep until light."

Luckily, not too far off, he spotted an abandoned snail shell, gleaming palely in the moonlight, and he curled up inside it, and settled down to sleep.

Just then, two thieves came walking along, discussing how they might rob the rich parson's house, just down the road.

"I know how you could do it!"

"Who said that?" one of the thieves asked.

"Down here, at your feet!" Thumbling called out.

The thief squatted down, to get a closer look. When he saw how small Thumbling was, he burst out laughing. "How could

you help us?" he asked.

"Well," Thumbling said, "I could fit through the iron bars over the parson's windows, and just hand the goods out to you."

After a moment's thought, the thieves realized that was a pretty good plan, so they scooped him up and took him along.

When they got to the parson's house, they held Thumbling up to the parlor window, and he slipped in between the bars. Once inside, he called out to them, as loud as he could: "What do you want me to give you?"

The thieves tried to shush him. "Be quiet!" they said, "or you'll wake the people up -- just hand us whatever you can reach."

But Thumbling continued, as if he hadn't heard them correctly. "

What do you want?"

The thieves were starting to panic. "Be quiet, please!" they begged him.

Sure enough, the housemaid was sleeping in the next room, and woke up, thinking she'd heard something.

"Okay, okay," Thumbling said, "Just hold your hands up to the window."

And so the thieves did.

"My!" Thumbling said, in his full voice again, "this house is full of nice things! I will steal all of them!"

The housemaid definitely heard that, and hurried from her room into the parlor.

The two thieves ran off into the night, as the Wild Hunt were after them.

The housemaid looked around the parlor, but couldn't see where the voice had been coming from. "I must have been sleepwalking again," she said to herself, "and dreamed the whole thing."

Meanwhile, Thumbling slipped out the parlor door, and headed to the barn. There, he crawled into the hay bale, where it was warm and dry, and went to sleep. He was still sound asleep when the housemaid went out to feed the cow, and took up a great load of hay (with Thumbling in the middle of it), and put it in the manger.

And the cow took him up in her first mouthful.

"Oh, my!" Thumbling said, "how did I get caught in the mill?" Then, he realized where he was, and, dodging the teeth to avoid getting ground to bits, he dove down her throat, and into her stomach.

"This is a very dark room," he said. "They forgot to put in any windows. I could do with a candle."

The cow kept eating, and the hay kept coming down, and Thumbling was feeling rather crowded.

"No more hay!" he called out to the cow, "No more hay!"

(If the cow heard him, she paid no attention)

The maid, meanwhile, was milking the cow. And she heard Thumbling calling out: "No more hay! Please -- No more hay!"

The maid was so astonished that she jumped off her stool, and knocked over the milk bucket, too. She ran to the parson and exclaimed: "The cow's talking! "

At first, the parson didn't believe her, and said she must be crazy. But in the end, the maid convinced him to come to the barn and see for himself. When he did, he declared that the cow must be possessed by demons, and should be killed on the spot. And so the cow was slaughtered, and the entrails (with Thumbling still inside) were thrown on the dung heap.

Thumbling then started to crawl his way out. And he'd almost made it when a lone wolf came along and swallowed the cow's stomach whole, Thumbling and all.

So now, he was in the wolf's stomach. "Perhaps I could talk reason with this wolf," Thumbling thought to himself, and so he spoke up: "That cow's stomach made a poor breakfast, I venture," he said.

And the wolf agreed that it had.

"If you're still hungry," Thumbling suggested, "I know where you can get a fine meal." And he described the way to his own house. "Its cellar is full of ham and mutton, and jellies, and cakes; you could have a great feast, there!"

The wolf scoffed. "And how am I to get in?" he asked. "It's not like they'll open the front door to me."

"Oh, you don't need the front door," Thumbling said. "There's a window right at ground level, where there's a gutter alongside the house. You could slip in there, and no one inside would be the wiser."

So, the wolf hurried off to the house Thumbling described. He found little window, slipped inside, and found all the food Thumbling had described, too. And he began to eat, and eat, and eat, until he was full.

That's when Thumbling started to jump, and dance, and shout inside the wolf's belly.

"Oh, be quiet,

please!" the wolf said, "or you'll wake the people!"

"No," said Thumbling. "You've had your chance to feast and party -- now, it's

my turn!" And he jumped and shouted even more.

The wolf panicked, and tried to climb back out the window. But he'd eaten too much, and was now too fat.

The sound of the wolf thrashing around in the cellar alerted the woodsman and his wife. And when he peeked through the door and saw that a wolf had gotten in, he grabbed the ax, and handed his wife the scythe. "I'll go for its head," he said to her, and if I don't kill it, you use the scythe, just to be sure."

But as they were coming down the stairs, Thumbling called out: "I'm here! I'm inside the wolf!"

So the woodsman waved his wife aside. He'd have to make sure to kill the wolf in one blow, so as not to harm his son inside. And with one blow he cut off the wolf's head.

Then they very carefully cut open its stomach, and let Thumbling out.

"See, Father?" the boy said. "I told you I'd come home safe again."

"Where have you been?" his parents asked him. "You have no idea how sick we were with worry for you, all night long."

"I've been all around the world," he said: "I've been down a mouse hole, and in snail shell, and a cow's stomach, and then a wolf's stomach. But I'm done with traveling, and I'll stay home."

Then, he had a big breakfast, and a bath. And his mother made him a new set of clothes, because the ones he'd been wearing were spoiled beyond repair.

The End

Looked at from a somewhat literal perspective, this story can be seen (if you'll pardon the idiom) as a tall tale about living life with dwarfism. But as an allegory, it can speak to the lived experience of children growing up with all sorts of physical impairments, including cerebral palsy (and the detail that he was born two months premature is certainly suggestive of CP).

It starts with the negotiation around chores, and figuring out ways to fully participate in family life. At first, Thumbling's parents see him

only as someone to be doted on and protected, but with just a little bit of help with the things he absolutely cannot do, and an unconventional approach to the rest, Thumbling is able to be a full partner in his father's work.

At first glance, it may seem that the triggering event of the plot -- Thumbling's negotiation of his own sale into slavery -- is a barbaric practice of olden times. But these are issues families of the disabled have to face on a regular basis even today: whether or not to sign the release form allowing your child to be on a poster for a charity event (which you know will end up being pity-porn, but help raise money for adaptive equipment you can't afford, otherwise), just for one example.

The "running joke" of Thumbling's supposed invisibility is also part of the lived experience of disabled people. I have often been right beside some people, talking to them in full voice, only to have them talk over my head to the able-bodied person who happened to be standing near me. Or I've been dressed in a skirt and blouse, and

still referred to as "he," because of a person's squeamishness at the possibility of actually

looking at me.

Thumbling uses this "invisibility" to escape those who would abuse him. And, at first, he fains "simplicity" in not understanding (and thus, ignoring) others' demands for him to be quiet. And such so-called 'trickery' is still needed, sometimes, when people with disabilities are in an abusive or threatening situation, and can't fight back or run away. But his moment of freedom comes when Thumbling refuses to be quiet, and says: "It's my turn, now!" And so it is for those of us in the real world: Our time of being invisible is coming to an end.